Alexandria, VA — Railroading is one of America’s oldest and best infrastructure stories, from the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 to the numerous engineering marvels that spread across the nationwide rail network today. These infrastructure achievements are not only admirable for their engineering, but also for the way they connected a growing nation and continue to connect communities and economies coast to coast.

We’re taking a closer look at just a sample of these marvels for Infrastructure Week 2020 (September 14-21). With projects spanning from 1854 to 2019, railroading in America is truly a story of the past, present and future.

Union Pacific’s Tehachapi Loop

Kern County, California

Opened by the Southern Pacific Railroad in 1876, the Tehachapi Loop is a spiral, or helix, section of track just under a mile long through the Tehachapi Mountains in south-central California near Bakersfield. Today the loop, averaging about 40 trains a day, is part of Union Pacific’s Mojave Subdivision. The frequency of its trains combined with the scenery and fact that any train longer than 4,000 feet will pass over itself while going around the loop make it a popular spot for railfans. Rising at a 2 percent grade, Tehachapi was an engineering wonder of its day and remains relatively unchanged 144 years after it was built, earning a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark designation in 1998.

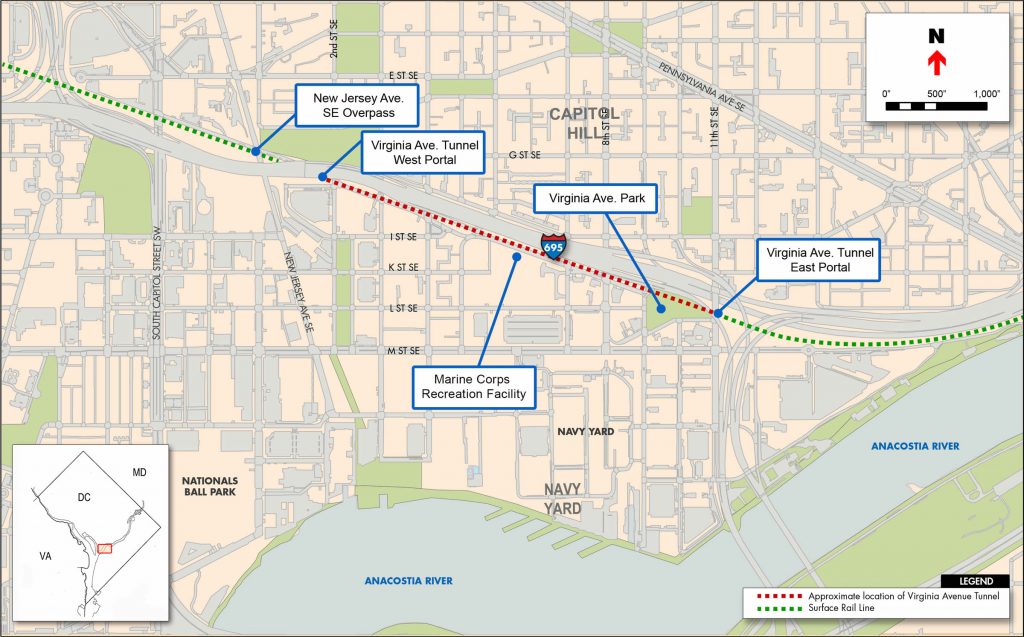

CSX’s Virginia Avenue Tunnel

Washington, D.C.

Cutting through the nation’s capital since it was originally constructed in 1872 by the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad, the Virginia Avenue Tunnel is now part of CSX’s RF&P Subdivision running from Washington, D.C. to Richmond, Virginia. In 2015, CSX began construction to augment capacity on the critical freight artery by adding a second tunnel as well as extending the tunnel’s original height to accommodate double-stacked intermodal railcars. The project, particularly challenging given the historical context and urban setting, earned the 2019 “Project of the Year” from the Engineering News-Record after its completion.

CN’s Aquatrain

Prince Rupert, British Columbia to Whittier, Alaska

The largest railcar barge in the world, CN’s Aquatrain provides vital, bi-weekly service connecting Alaska to the rest of North America year-round via the shortest water route by 600 miles. While CN has offered this ferry service since 1962, the Aquatrain was built in 1982 and allows railcars to travel intact from origin to destination on one bill of lading. The 400-foot by 100-foot barge features eight sidings, fitting some 50 railcars that would extend to nearly 3,000 feet if placed end-to-end. On its arrival in Whittier, Ala., cargo can be interchanged with the Alaska Railroad and railed to Anchorage and Fairbanks and trucked beyond Fairbanks to Prudhoe Bay and the Alaska North Slope. The Aquatrain is one of the ways that commodities from across North American—like orange juice from Florida!—can travel all the way up to the farthest points of Alaska.

Kansas City Southern’s Texas Mexican Railway International Bridge

Laredo, Texas

Vital to facilitating trade with America’s third-largest trading partner, KCS’s Texas Mexican Railway International Bridge is one of six rail-only bridges that span the southern border. The truss bridge—a structure comprised of triangular units—was completed in 1920 and today is still a critical connection for KCS between Laredo on the U.S. side and Nueva Laredo in Mexico. Some 23 to 30 trains traverse the bridge each day, recently prompting plans to construct a second adjacent international bridge that will expand capacity for trade, especially important as the U.S., Mexico and Canada continue their crucial trade relationship via the recently enacted USMCA trade agreement.

Norfolk Southern’s Horseshoe Curve

Blair County, Pennsylvania

A railfan attraction since the late 1800s, Horseshoe Curve in west-central Pennsylvania is a three-track railroad curve on Norfolk Southern’s Pittsburgh Line that allows trains to traverse the Allegheny Mountains. It was completed in 1854 by the Pennsylvania Railroad after four years of labor using no heavy equipment, cutting travel time between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh from days to hours. Chief Engineer John Edgar Thomson achieved a gradual 1.34 percent grade via the horseshoe shape, an engineering feat at the time and one that has received many distinctions including designations as a National Historic Landmark and National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Civil Engineers.

BNSF’s Cascade Tunnel

Stevens Pass, Washington

At 7.8 miles in length, the Cascade Tunnel is the longest railroad tunnel in the U.S. today and was the longest in the Western Hemisphere when it was completed by the Great Northern Railway and dedicated by President-elect Herbert Hoover in 1929. The project, which involved moving 934,600 cubic yards of rock and earth, took three years and was undertaken to replace the original Cascade Tunnel that had been afflicted by snow slides. Located in the Cascade Range in Washington 60 miles east of Seattle, the tunnel is currently part of BNSF’s Scenic Subdivision connecting Berne and Scenic Hot Springs as well as Amtrak’s Empire Builder line, running a maximum of 28 trains per day.

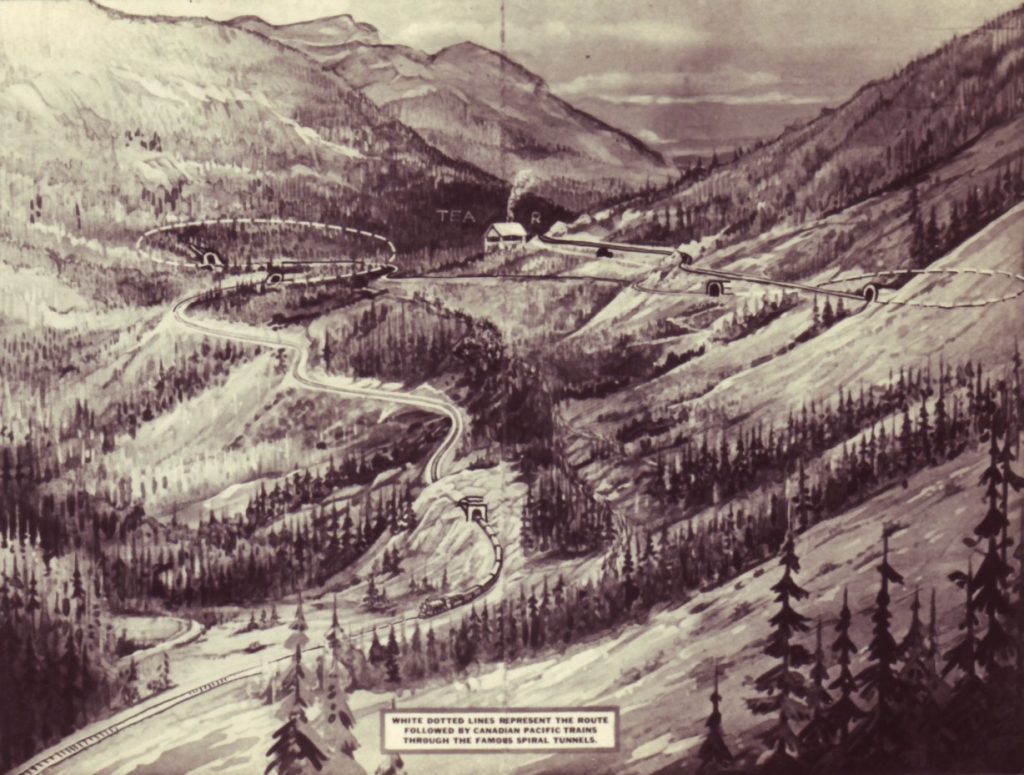

CP’s Spiral Tunnels

Kicking Horse Pass, British Columbia

Nominated by the CBC as one of the “Seven Wonders of Canada,” CP’s famous Spiral Tunnels were an engineering solution to the challenge of traversing Kicking Horse Pass across the Continental Divide of the Americas near the Alberta-British Columbia border. The spirals, completed in 1909 as a replacement for the “Big Hill” route, are two three-quarter circles carved into the valley walls of the pass. Lengthening the track eased the new route’s grade to 2.2 percent from what had previously been the steepest stretch of main-line railroad in North America, making the journey less harrowing and reducing scheduling delays. The sight of a single train spiraling over itself—the engine emerging from one tunnel while its tail is still entering the tunnel below—is one that attracts railfans and tourists from all over North America.